Two-Factor Authentication Considerations for e-Prescribing of Controlled Substances

The primary objective of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) interim final rule allowing electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS) is to reduce the potential for diversion and subsequent abuse of controlled substances, so the DEA ruling stipulates that certain requirements must be met before an organization can enable EPCS.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that the success of an EPCS project largely depends on clinical adoption. So, it is important to make technology decisions that meet regulatory requirements, improve clinical workflows, and minimize interruptions and inconveniences to prescribers.

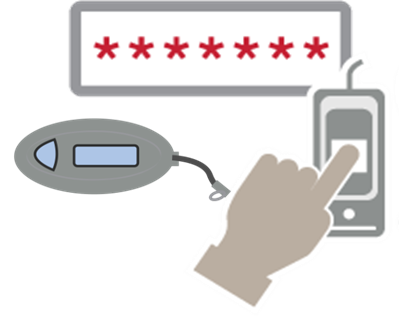

One of the most important technology decisions you need to make when developing an EPCS project plan is which multifactor authentication method to use. As, two-factor authentication is required by the DEA for electronic prescription signing of controlled substances. If the two-factor authentication modality you choose does not fit easily into clinical workflows, providers will resist EPCS. Such resistance will put your entire EPCS project at risk.

The DEA rule states that two of the three following authentication modalities should be used for prescription signing: something the provider knows, something the provider has, and something the provider is. A common question we hear is whether a username and password combination already constitutes two-factor authentication. The DEA ruling points out that “combinations of user IDs and passwords are one-factor because they require only information that you know.” So, an additional authentication modality is required for EPCS.

Which factors best fit your organization’s EPCS needs depends on what is most convenient for your clinical workflows, and how/when/where EPCS will take place within your organization. For example, in our experience, fingerprint authentication is widely accepted by providers, especially in areas with a high rate of prescribing controlled substances such as Orthopedics, the Emergency Department, or Trauma Centers. In these areas, and in other, similar areas, providers may be writing 40-60 prescriptions per day, and fingerprint biometrics (in addition to a password as the second factor) is the most efficient and user-friendly option for them. On the other hand, tokens typically work well for allowing providers to write prescriptions remotely.

Important EPCS Two-Factor Authentication Considerations

In addition to clinical workflow requirements, other important factors to consider when selecting two-factor authentication modalities for EPCS include:

- Passwords: For the purposes of EPCS, the DEA ruling essentially defaults to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to define password strength. Many hospital IT executives I speak with believe that if their organization were audited, the DEA would look for a minimum eight-character password using all three of the four common groups: uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols.

- Biometrics: The common understanding of the ‘something you are’ modality for two-factor authentication is a biometric identifier such as fingerprint, a facial recognition scan, an iris scan, or a voice pattern. It is important to note that the DEA does not specify what kind of biometrics can be used for EPCS, only that they must meet FIPS-201 Personal Identity Verification (PIV) requirements and have a false match rate of less than 1 in 1,000. Today, fingerprint biometric identification is best suited to meet these requirements. But, not all fingerprint readers meet the DEA requirements for EPCS. For instance, readers built-in to most laptops are swipe readers and are not FIPS-compliant, and therefore cannot be used for EPCS.

- Tokens: One-time password (OTP) hard and soft tokens can be used as an authentication modality for EPCS, but only if they meet FIPS 140-2 standards. While prescribers within the hospital or clinic tend to prefer fingerprint biometric identification, tokens are often more practical for remote e-Prescribing. For, when working remotely, it is easy for providers to use a smartphone application to generate OTP soft tokens. While the added step of generating a token slows down a provider’s workflow in high-traffic, busy areas of the hospital, it is a good solution for remote e-Prescribing, when providers may not have access to a FIPS-compliant fingerprint reader.

- PKI Smartcards: Smartcards (but not proximity cards) are also allowed by the DEA as a two-factor authentication modality for EPCS, but healthcare organizations are generally reluctant to use them for a number of reasons. Smartcards are not typically designed to be frequently inserted into card readers. Such frequent use is required for EPCS, especially for providers who prescribe higher volumes of controlled substances. Constantly inserting a card impacts providers’ user experience and adds cost. Smartcards also require a card management system and most certificates expire after one year. These restrictions and renewals add more costs. From a workflow perspective, smartcards can be lost easily, are often forgotten inside their card readers, and are difficult to use remotely.

These are just a few considerations to keep in mind when deciding on which two-factor authentication modalities to use for EPCS. By starting with a clear understanding of the different clinical workflows for EPCS—including when and where e-Prescribing will take place within your organization— you can develop a plan to deploy an easy-to-use, intuitive solution that will boost provider adoption of EPCS. Ultimately, provider satisfaction and adoptions rates will make, or break, your EPCS efforts. For, providers are the people who have to endlessly repeat EPCS processes for every controlled substance prescription and refill.