Common Overlooked Steps and Key Considerations to Enabling e-Prescribing of Controlled Substances

As we discussed in our last post about secure electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS), the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) passed a ruling in 2010 allowing controlled substances to be prescribed electronically—if specific criteria are met by all parties participating in e-Prescribing. These criteria include:

1. EPCS must be authorized by the state board of pharmacy

2. The electronic medical records (EMR) system must be certified for EPCS

3. The pharmacy must be certified to accept prescriptions for controlled substances electronically

4. Two-factor authentication technology (using modalities defined by the DEA) must be used to authorize the prescriber. If one of these modalities is biometrics, the DEA requires that the biometrics application provider be certified by an independent third-party testing firm.

These criteria have, for the most part, been satisfied and healthcare organizations are able to adopt EPCS in virtually every U.S. state. While we are seeing increasing interest from customers in enabling EPCS, there are still a number of steps to the process that get overlooked.

For example, customers using Epic need to implement several technology components for EPCS, including the setup of a FIPS 140-2 Web server. In addition, they need to implement new Surescripts application programming interfaces (APIs), engage their local pharmacies to make sure they are able to accept prescriptions for controlled substances electronically and identify a third party that is authorized by the DEA to perform an audit of the configuration once it is complete. Here are a few more considerations and common overlooked components as

organizations look to complete their EPCS puzzle.

Project Scope—Organizations should complete an audit of all the orders providers are currently processing, which can be eye-opening. For example, one organization’s audit revealed that it averaged about 7,500 orders per doctor, per month. Reports indicate that about 11 percent of prescriptions are for controlled substances (although some customers tell us it is as high as 18 percent in their organizations). For this particular customer, that conservatively equates to more than 800 controlled substance orders per doctor, per month. In addition, in October 2013, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) stated that it plans to recommend to the Department of Health and Human Services that hydrocodone-based medication like Vicodin should be reclassified from a Schedule III to a Schedule II drug. When moving to EPCS, these two factors will likely have a huge impact on the right mix of two-factor authentication modalities as well as the backend infrastructure used to handle it.

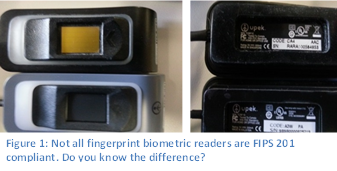

- FIPS Compliant Fingerprint Readers—Many organizations are already using fingerprint biometrics for logins and/or second-factor authentication. Unfortunately, many of these fingerprint readers were deployed before the DEA’s final EPCS rule, which mandates that readers for EPCS be FIPS 201 compliant. Most fingerprint readers deployed before mid-2012 are probably not FIPS-201 compliant and cannot be used for EPCS transactions. Similarly, until very recently, the fingerprint readers that are built into most laptops are also not FIPS 201 compliant. When considering EPCS, organizations should identify if their fingerprint biometric readers meet DEA requirements and if not, implement a plan for deploying readers that are allowed for EPCS.

- Other Authentication Modalities—In addition to fingerprint biometrics, the DEA allows specific types of tokens as an accepted means of second-factor authentication for EPCS. Any one time password (OTP) delivered as a token must be secure (which, for the most part, excludes options like SMS text or phone calls). What’s more, providers may need to carry a separate token for each disparate organization where they will e-Prescribe controlled substances. This has the potential to be confusing and cumbersome for providers who practice in several different healthcare organizations, which is something that should be considered when developing an EPCS plan.

- Enrollment—A significant portion of the DEA rule for EPCS is devoted identity proofing. Many organizations we speak with interpret this to mean that they will need specific credentialing offices or individuals who will physically check the identification of the provider, verify their DEA number and then supervise the enrollment of the fingerprint or token. If using fingerprint biometrics, however, enrollment must be done on a FIPS 201 compliant reader. So, if an organization is already using fingerprint authentication on an older, non-FIPS compliant reader, their providers will need to be re-enrolled to be authorized for EPCS.

- Back-end Infrastructure–After an organization completes the audit recommended above, it must evaluate whether its back-end infrastructure can handle the volume of e-Prescription transactions. For example, if choosing an authentication modality that requires a certificate authority (CAs), the server which manages CAs must be equipped to handle the added load. In the case noted previously, the customer realized it would average seven transactions per second.

These are just a few of the overlooked items and misperceptions some organizations have when developing their plans for secure e-Prescribing, especially for controlled substances. In the coming weeks we’ll dive deeper into these and other topics to provide insight, tips and best practices on how to navigate the requirements for EPCS and start realizing the benefits. If there are any specific topics you are interested in, please leave a comment here and we’ll be sure to address it.