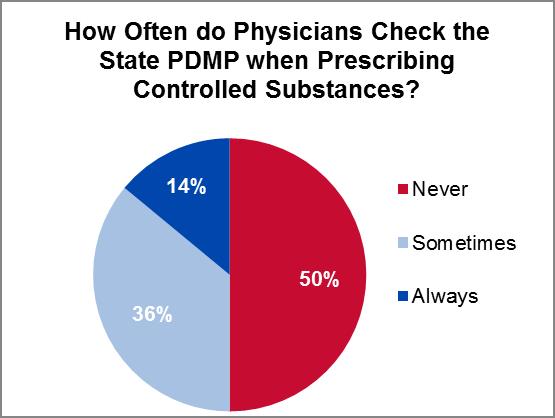

Survey: 50% of Physicians Never Check the PDMP when Prescribing Controlled Substances

America is facing a national public health crisis: prescription drug abuse.

Overdoses of prescription medication contribute to more than 22,000 deaths per year, the majority of which involve opioid painkillers like Vicodin and OxyContin. Fatalities from these highly addictive drugs have increased nearly fourfold in the last decade and lead to more deaths per year than cocaine and heroin combined.

The DEA estimates that about 7 million Americans abuse controlled substances, and as an emergency physician, I watch this crisis unfold firsthand. The number of addicts I encounter who are “doctor shopping” for pills is staggering, and tragically, I am far too often treating patients who have overdosed on medication.

In an effort to curb drug diversion and abuse, many states have implemented prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which are electronic databases that collect information on medications dispensed in that state. PDMPs are designed to identify, deter or prevent drug abuse and diversion as well as to support access to controlled substances for legitimate medical use.

While I applaud the effort to curb the prescription drug epidemic facing the U.S., the challenge with PDMPs is getting prescribers to use them. According to a recent survey of 192 U.S. physicians, 50 percent of respondents indicate they never check their state PDMP when prescribing controlled substances.

The remaining respondents only check the database about 48 percent of the time when prescribing controlled substances. In fact, only 14 percent of physicians indicate they always reference the PDMP.

There are a number of reasons why this may be the case. For instance, not every state requires prescribers to check the PDMP, and in today’s hectic healthcare environment, it is not uncommon for providers to avoid processes that aren’t mandatory (especially if they have the potential to slow down workflows).

In addition, many clinical applications as currently designed and implemented are complex, are difficult to use or have poor interfaces (in fairness, this is not a challenge exclusive to PDMPs). This can be very frustrating and detract from patients, and despite reports to the contrary, providers are generally not averse to technology…so long as it does not get in the way of care delivery.

Without question, the concept of a PDMP can work. Just last week, I treated a patient who complained of chronic back pain and said all the right things to warrant narcotic treatment upon discharge from the ER. However, after checking the state PDMP database, we were able to discern that the patient had been to several other local hospitals recently and already received more than 100 tablets of oxycodone and hydrocodone.

However, in my personal experience (and as the findings of the Imprivata survey indicate), much work still needs to be done and PDMPs alone are not enough to put an end to prescription drug diversion.

Compounding the issue is the continued use of paper prescriptions, which can be altered or stolen. Fortunately, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) now allows electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS) in every state, which will help minimize drug diversion and fraud by creating a secure, auditable electronic transmission directly to the pharmacy.

EPCS also has a number of additional benefits, including:

- Improved provider satisfaction by eliminating dual prescribing workflows and minimizing potential exposure of a prescriber’s DEA number

- Improved patient satisfaction and safety by reducing wait times at pharmacies

- Increased e-Prescribing utilization to help meet Meaningful Use requirements

- Reduced prescription errors and inaccuracies

While there is no ‘silver bullet’ to preventing drug diversion and abuse, technologies like PDMPs, EPCS can be used together to begin to address the issue, but again, only if they are designed from the clinical perspective and enhance—not impede—the care delivery process. Ideally, providers would be able to link to and from these and other clinical applications from the EMR.

Healthcare leadership needs to work with providers to give them the processes and tools they need to enforce the tighter controls governing controlled substances to make them more difficult to obtain for illegitimate use, while at the same time making it easier to prescribe controlled substances to patients in need.

By doing so, we can make it far more difficult to obtain highly addictive prescription medication for illicit purposes without placing any undue burden on patients with legitimate needs, which is a win-win situation for everyone.